hannahpongratz

hannahpongratz.de

Hauptmenü:

Psychology in climbing

is about psychological effects and phenomena in the world of climbing, how they arise and their consequences. Part I-VI here.

PART VI: Stress in competition: On Lions, Zebras, and Pink Elephants

Everyone who has ever competed knows how stressful this can be. However, while some athletes break under the pressure and nerves, others thrive, climbing better than ever. This article is about why this happens, what goes on in your body in a stressful situation, how this influences your ability to perform in a competition, and finally how to better deal with it.

Some Definitions

The term “stress” is a little unfortunate as it is used for both cause and reaction. To avoid confusion, researchers have switched to the term stressor for the cause (in this case, the competition) and stress response for the reaction. Another important concept is the term “arousal”, which refers to a state of wakefulness, vigilance, and activation. On a physiological level, arousal corresponds to the activation of the sympathetic nervous system (see next paragraph). It is minimal during sleep, an extremely high level of arousal, on the other hand, is found during a panic attack.

What happens

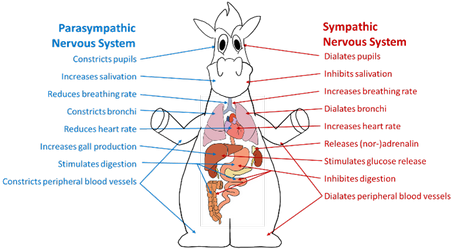

On a physiological level, a stress response is first and foremost the sympathetic nervous system in action. The sympathetic nervous system is a part of the autonomous nervous system, which regulates all bodily functions which are autonomous (surprise!), meaning they happen without us having to voluntarily control them. These include, for example, our heartbeat, breathing, digestion, and metabolism. In case of a stressor, the sympathetic nervous system releases adrenaline and noradrenaline (also known as epinephrine and norepinephrine) which causes all of these bodily functions to adapt in a way that helps deal with the stressor. If the sympathetic nervous system had a motto, it would probably be “Live (and preferably run) as if there is no tomorrow, because otherwise there probably won’t be one.” It is wasteful and doesn’t care about the long-term consequences of its actions. The only thing that matters is dealing with the current situation right here and now. Everything else can be dealt with later. The antagonist of the sympathetic nervous system is the parasympathetic nervous system, which deals with recovery and the long term. It is resourceful, works sustainably, and ensures that things that secure survival months and years from now are getting done.

A look at a lion that chases a zebra across the savanna illustrates the tasks of the sympathetic nervous system, as the stress response in mammals is geared towards dealing with all sorts of stressors through the “fight-or-flight”-response. For one, activity of the cardiovascular system increases, meaning heart rate, breathing rate, and blood pressure increase. Furthermore, energy, mostly in the form of glucose, is mobilized to provide fuel for the upcoming race. On the other hand, processes that are geared towards the long-term preservation of the organism, like digestion, healing, and growth are put on ice. To quote Robert Sapolsky: “You have better things to do than digest breakfast when you are trying to avoid being someone’s lunch.” Furthermore, extreme stress can inhibit the perception of pain, a phenomenon called stress-induced analgesia. This too makes sense from an evolutionary perspective, as pain is a warning signal that is supposed to keep us from doing things that harm us. In a situation of extreme stress, there is probably nothing so harmful, that we shouldn’t get out of the situation before dealing with it. As a zebra trying to escape the lion, it would not be a very good idea to protect a sprained ankle by limping. The sympathetic nervous system further has a number of influences on our perception and cognition. For one, our senses become sharper. That is the reason why the cracking of a branch might startle us when we walk through the streets alone at night although we wouldn’t even have registered the same sound during daytime. Furthermore, our attentional focus narrows, our thinking becomes less flexible and there is a tendency to stick to habits and rituals. This, too, is evolutionarily plausible: The escape from a lion might not be the best moment to test whether zebras can run backward.

In other words, the stress response, that is brought on by the sympathetic nervous system is extremely well suited to deal with the typical prehistoric stressor. As a competition demands maximal physical performance as well, the changes brought about by the stress response would appear to be helpful rather than harmful and this is indeed the reason why some athletes perform better in competition than in training. However, why does the exact opposite happen to some athletes? Two theories can help us understand this phenomenon. Both of these have not gone without criticism and have their weaknesses, however, in my opinion, they are still useful to understand what is going on in situations where you or one of your athletes struggles under pressure.

Yerkes and Dodson and Schachter and Singer

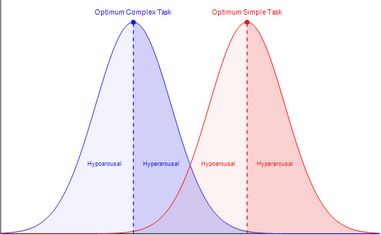

Robert Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson developed the Yerkes-Dodson-Law at the beginning of the last century. It states that the relationship between arousal and performance is best described by a bell-shaped curve. This means, that performance initially increases with increasing levels of arousal. However, past a certain point, the relationship reverses and further increases in arousal lead to a decrease in task performance.

Furthermore, the optimum differs between different kinds of tasks. It is lower for more complex and cognitively demanding tasks, while it is higher for straightforward and overlearned tasks. An example of the former in climbing is an onsight attempt in a delicate slab. The best example of the latter in climbing is speed (which might explain, why athletes post PBs in competition quite regularly). However, a redpoint attempt in a well-known and relatively straightforward boulder problem will most likely benefit from high levels of arousal as well. This association between optimal arousal and task type is mainly due to the aforementioned fact, that we tend to stick to our habits in stressful situations and save the thinking for later. The zebras that stopped and thought about whether there might be another option than running away were eliminated by evolution rather quickly. However, many of the tasks we are confronted with in our modern lives and during competitions demand that we think before we act. Another thing that can lead to a detriment in performance at very high levels of arousal is, that, in an extreme situation, the fight-or-flight response might be replaced by “freezing”. This is evolutionary speaking, the last resort. If fighting is impossible and it is too late to flee, freezing is the best thing left, since it at least doesn’t draw extra attention to oneself through movement. However, this is obviously not very helpful in a competition (and most other tasks humans are confronted with in everyday life).

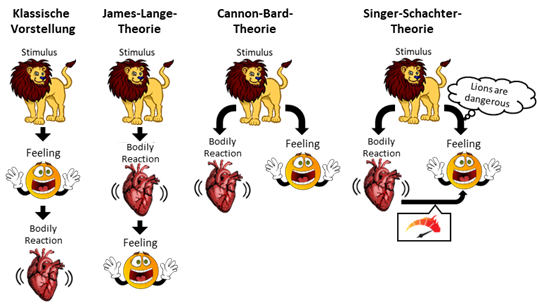

Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer were two psychologists, who (amongst other things) researched the emergence of emotions and developed the so-called two-factor theory, today often known as the Schachter-Singer theory. The idea most people have of how emotions work is that the perception of a situation gives rise to certain feelings (I see a lion -> I feel scared) which in turn can affect our bodily functions (I feel scared -> My heart is beating faster, I am sweating, etc.). The first psychological theory about emotions, the James-Lange theory named after their developers William James and Carl Lange, turned this idea on its head, claiming that the perception of a situation directly affects bodily processes, which are the basis for feeling a certain way. In other words, your heart isn’t beating fast because you are scared, you are scared because your heart is beating fast. However, this theory has some very substantial problems, so Walter Cannon and Phillip Bard developed the Cannon-Bard theory as an alternative (yes, there is a certain pattern to theory naming in psychology…). It proposes, that both feelings and bodily changes derive independently from perceptions of the situation (I see a lion -> I feel scared AND my heart is beating faster). However, this ignores all interactions between the body and how we feel, which is what Schachter and Singer tried to remedy in their theory. They proposed that the level of arousal, indicated by our bodily state determines the intensity of our emotion, however, which emotion we feel (sadness, fear, anger…) is determined by our cognitive construal of the situation (I see a lion -> Lions are dangerous -> I must be scared -> My heart beats fast -> I must be really scared). It follows from this, that the way in which someone construes a situation and labels their feelings has a huge impact on the way they experience this very same situation. Someone who interprets the typical signs of arousal in a competition as signs of anticipation and excitement will likely have a very different experience from someone who interprets them as signs of anxiety and helplessness. If arousal is attributed to a non-emotional source (e. g. an adrenaline injection), even high levels of arousal might not cause feelings of any kind. As physical activity itself increases our level of arousal, parts of the arousal during competitions are due to the activity during the warm-up and the climbing itself. If athletes are not aware of this, they might falsely attribute this arousal to their nervosity and anxiety, potentially escalating the situation further.

Strategies to regulate arousal

- Acceptance

The first step in regulating your arousal and nervosity is accepting it and viewing it as something potentially helpful. As described above, the stress response is designed to facilitate peak performances. It only becomes a problem, if athletes are afraid of being nervous, so they don’t just get nervous and stressed by the competition they also get nervous and stressed by being nervous and stressed. This creates a vicious circle and the arousal rises to a level, that is not conducive of performance anymore. As a reaction, athletes often try to calm themselves down by telling themselves to not be nervous. That is, however, about as effective as trying to not think about a pink elephant by thinking about not thinking about a pink elephant. In other words, it's probably the worst thing to do.

- Distraction

Everyone that has ever been confronted with the pink elephant probably knows, that there is only one real possibility to not think about the elephant: Distracting yourself with other thoughts. Similarly, it makes sense to distract yourself from your nervousness by focusing your attention on something else. For waiting periods before and during the competition, this could be anything from reading a book or watching a movie to learning for an exam. It should, however, be cognitively demanding enough to capture your full attention. During the warm-up etc. the most sensible thing is to focus on what you are doing and doing it as well as possible. This has the additional advantage of ensuring that you warm up properly. However, you shouldn’t assume, that you won’t get nervous as a consequence of doing this. The pink elephant will show itself occasionally. But as long as you don’t feed it by stressing out about being stressed, it will not trample the whole place down.

- Habits

Competitions, at least in part, are stressful because they are unfamiliar and unpredictable. In all of this chaos, habits and rituals can provide safety. Habits might be anything from the complete warm-up program to small rituals prior to an attempt, like patting off chalk on your pants or taking a deep breath. These habits work because you’re essentially signaling to your brain: I know how this works and I know what to do. Thus, it makes sense to establish such habits and routines in training early on so you can fall back on them during competitions. You should, however, be careful to only choose habits that are viable in competitive situations. This can be especially tricky in regard to the warm-up, as the warm-up facilities are often much more restricted in competitions than it is in everyday training. Therefore, you should think about which routines are feasible early on and consistently practice them in training. As mentioned earlier, under stress we tend to do what we always do anyway. Therefore, good habits are doubly helpful, since they eliminate the need to continually override any bad habits we may have acquired.

- Preparation

Competitions are indeed unpredictable to a degree (hello, last-minute changes to the schedule…), however, they are not completely random. Therefore, it makes sense to reduce unnecessary uncertainty by being well-prepared. That means, for example, when the competition begins (for you), knowing how long it takes you to warm up and consequently when you have to start warming up. Ideally, you can find out what warm-up facilities are available beforehand. If this isn’t possible you should at least have plans for how to warm up in different circumstances. The basic principle is always that all decisions and preparations that can be made beforehand should indeed be made beforehand. A packing and to-do list as well as a schedule can be very helpful for doing this.

- Breathing

Breathing is a special case of the functions controlled by the automatic nervous system because unlike the others we have some degree of voluntary control over it. We can hold our breath, but not our heartbeat. However, as the connections from our body to our brain are bi-directional, we can influence our autonomic nervous system and thereby our level of arousal by consciously controlling our breathing. As the sympathetic nervous system is activated by breathing in, we can heighten our level of arousal by focusing more on inhaling. On the contrary, our parasympathetic nervous system is activated by breathing out, therefore we can lower our level of arousal by focusing more on exhaling. (If you want concrete instructions, there are literally hundreds of videos on YouTube, that will guide you through breathing exercises, however, there are no magic numbers you have to adhere to.)

- Physical activity

(Intense) physical activity is a great way to increase your level of arousal. This can be especially useful at the beginning of the warm-up, especially if a competition starts very early or in cases where there is a long break between rounds and the body has essentially “shut down” again. From experience, I have found that physical activity is also a good outlet for excessive arousal, especially in the time between warm-up and the start of the competition. By moving and being active during this time you can essentially give your brain an alternative way of interpreting the arousal, namely as a consequence of the activity and not as nervousness or anxiety.

For parents, coaches, etc.

If you’re not an athlete yourself but a “support person”, there are also a few things you can do to help.

- Do not show your own stress

The first couple of times I was at a competition as a coach, I was so nervous, I felt like I was about to have a heart attack and many other parents and coaches have probably had similar experiences. The problem is that these feelings can transfer to the athletes. Those first couple of times I probably did more harm than good. However, by now I have (mostly) learned to not show the stress and anxiety I feel. The emphasis really is on “not show” because ultimately all that matters is what the athletes perceive, not how you really feel. You don’t have to climb after all. For parents that might even mean, removing themselves from the competition altogether.

- Support

As mentioned, being well prepared helps enormously to deal with the stress of competing. You can help athletes to do so by aiding them in their preparations and doing as much as possible for them. For example, you might do the registration for them, remind them how much time is left to the start and at what point they have to start warming up, remind them to eat and/or drink and get them the stuff they need. However, you should talk about who does what and what they want and don’t want help with beforehand, otherwise, the result is probably more chaos and stress.

For anyone, who is interested in this topic further, and especially the biological basis of stress, you might want to check out the book “Why zebras don’t get ulcers” by the aforementioned Robert Sapolsky. As you may have guessed from the book’s title, he coined the lion-zebra-metaphor. The book goes into the biological mechanisms of stress and its short- and long-term consequences in great detail. However, it is still written in a way that is understandable to anyone who hasn’t studied biology or psychology.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

PART V: The Penelope-Effect: When less is more

Climbers seem to have a weird tendency towards self-destruction. They squeeze into shoes that are at least two sizes too small and continue climbing until blood is dripping from their fingertips. And they even take pride in that. Some might say that’s a “hard-core mentality”, but you could call it masochism as well. However, aside from the question of whether that’s a desirable culture in sports, there is a problem with the approach of training to complete exhaustion every time you enter the gym. Sessions in this mindset usually end – more or less literally – with one crawling towards the wall on all four and just refusing to let go, until one (hopefully) reaches the top. In doing so, it may very well be, that you reach a few more top holds – which unfortunately reinforces the behaviour. Most certainly, though, this will be done with a technique that leaves much to be desirable. The real problem, however, is not that you did these specific climbs in an unsightly manner, but that you will learn and internalize this technique. As – to slightly rephrase a quote from Paul Watzlawick – you cannot not learn. Consequently, you might undo all the technical progress you have made and might even be worse off after the session than beforehand.

This effect is named after Penelope, the wife of Odysseus. During her husband's journey, she was courted by various suitors. To delay remarrying, she claimed to be weaving a shroud and said she would remarry when she had finished it. However, every night she pulled out the threads and undid the work of the day, so the shroud was never completed. Essentially the same thing happens – although unintentionally – if you continue climbing in an overly fatigued state: Because the bad technique is learned, the work done previously is undone.

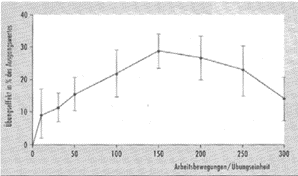

Figure 1 - Hollmann H, Hettinger W. Sportphysiologie. Springer-Verlag Heidelberg (2000)

In laboratory studies, the effect is usually isolated by giving subjects an easy motor task and varying the number of practice trials they do. One exemplary result of such a study is shown in Figure 1. In this case, the performance of those subjects, that had done 300 practice trials per session was essentially the same as the performance of subjects, that did a meagerly 50. In other words, the subjects in the 300-group essentially did 80% of their practice in vain. Not a very good track record. Furthermore, they performed significantly worse, than the participants, who did 150 practice trials per session. That means, that about half of their practice was not only not beneficial, it actively harmed their performance. Again, not what one would hope for.

This becomes especially problematic if the bad technique is overlearned to a point, where it becomes completely automatized[1], as such habits are incredibly hard to unlearn. This is something, that musicians and a couple of other sports have long known, which is why there is so much emphasis placed on beginners practicing with correct technique from the very beginning.

The conclusion is clear: Continue climbing only as long, as you can stay technically clean. The moment your technique starts deteriorating, the session should be done. So far, so good. However, you might have two (and a half) objections:

1. BUT I have to train to get stronger. Of course, that’s true. But that harks back to a distinction, that, in my opinion, is done way too seldomly in climbing: The difference between practice and training. When I say practice, I mean everything that is aimed towards improving one’s technical and tactical abilities. When I say training, however, I am talking about everything that is supposed to enhance one’s physical abilities[2], mainly strength and endurance. Of course, too much training can also harm progress in these physical capabilities (overtraining, injury risk, etc.). Nonetheless, in order to be effective, training has to induce a certain amount of fatigue. If you stop your endurance training, as soon as you start getting pumped, you misunderstood something. Practice, however, should stop, as soon as your performance begins to decline. At first glance, this seems to lead us into a dilemma: I should stop climbing if I start to fatigue, but I also have to continue, because the fatigue is necessary for my training to be effective. There is a rather simple solution though: Separate practice and training by using other modalities besides climbing, that is strength training. This minimizes the negative impact of the reduced quality of movement on your climbing since the transfer – both positive and negative - between any two activities is largely dependent on their similarity. Furthermore, the technique in those more isolated movements is usually less affected by fatigue in the first place, as the movement patterns are simpler.

2. BUT I have to climb in a fatigued state during competitions. Of course, that’s also true. But – at least I assume that – you don’t want to climb badly. You cannot improve your ability to climb well technically under conditions of fatigue in a competition, by doing the opposite in your practice. Instead, you should aim at automatizing your good technique to a point, where it persists even under fatigue. Furthermore, you can practice dealing with the effects of fatigue by occasionally climbing in such a state while completely focusing on remaining technically accurate. However, since this requires a very large amount of focus, this should be done sparingly.

2.5 BUT I like climbing a lot a lot. Well, I do too. This is also why I have been guilty of climbing in a very fatigued state with very sloppy technique time and time again, despite knowing the consequences. But that’s the point. I knew what I was getting into, and I made an informed choice. Plus, I know, I can’t do this too regularly if my goal is to improve. If your goal is different and you just want to have fun, I’m not here to tell you what you can and cannot do. Just don’t fool yourself.

[1] This will be most likely to occur if a big part of the time you spent climbing is in a fatigued state or you never make any attempts at correcting the acquired behaviour.

[2] Other people might use different terms, these are simply the ones I prefer. However, the concept remains the same

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Part IV: Self-Handicapping: Schrodingers cat in the climbing gym

When I first started competing on the national youth circuit, I noticed something quite odd. Again and again, I overheard athletes claiming that they were training only once or twice a week, among them some of the most successful ones in their respective categories. On one hand, that made me slightly envious. These people seemed to have an incredible amount of talent since they were able to get to that level with such little training. But I was also very much confused by the fact that they almost seemed to be proud of training so little. I have always been someone who values working hard and therefore I was proud of all the time and effort I put into my training. It took me a couple of years to understand what was going on and that behaviors I observed elsewhere essentially followed the same pattern. It took me even longer to learn that I wasn't the first person to notice this weird phenomenon but that there was a whole field of research in psychology on it, where these behaviors are called self-handicapping.

I previously mentioned self-handicapping in my article on self-fulfilling prophecies as a mechanism by which such prophecies can work. But self-handicapping is a lot more than that. In that previous article, I defined self-handicapping as behaviors that undermine one's capabilities in order to excuse a potential failure in advance. But that isn't quite the whole story. Self-handicapping refers to any behavior that impairs performance in order to make this performance seem better. Whether that means a failure doesn’t hit quite as hard or a good performance appears even better is irrelevant. A lot of times both mechanisms are at work at the same time: If the performance is bad, it can be excused. If, however, despite the handicap, the performance is good, even more impressive. Nevertheless, I will primarily focus on the use of self-handicapping in anticipation of a failure, since there is more research on it and my experience indicates that fear of failure is the more common cause for using self-handicaps.

Self-handicapping can express itself in a variety of ways. Avoidance of training is a very common example in sports. A lessened version of this is not trying as hard as possible. Other popular variants are claiming / showing off physical handicaps such as injuries (preferably demonstrated by various tapes across the body) or psychological handicaps like competition anxiety.

Those behaviors can be classified along two dimensions. First, there is the difference between acquired and claimed handicaps. That means psychologists distinguish between whether the person objectively acquired the handicap through their behavior (e.g., one actually avoids training) or whether they simply claimed that this was the case (e.g., one downplays how much they training they did. I for one have my suspicions which of these was the case back at those youth cups).

The second dimension is the distinction between internal and external handicaps. If my climbing shoe is completely worn out but I do not get new ones in time for a competition, that is an external (and acquired) handicap. However, if I claim to have competition anxiety that is an internal (and claimed) handicap since it is “inside” of me.

These two dimensions can be combined in any way, although some combinations are more common (e.g. internal handicaps are usually claimed since they are hard to observe from the outside). The distinction between these different types is useful since, although they work in the same way, they have slightly different characteristics.

So, as mentioned, self-handicapping is essentially an excuse in advance. But that excuse isn't an end in itself. The ultimate goal is to maintain a positive image of oneself and one's capabilities – in front of others as well as in front of oneself.

To achieve that the cause of a (potentially) bad performance is shifted from a central part of one's self-concept to a more peripheral one, meaning one that isn't valued quite as highly by the person. This is done as there isn't usually a perfect handicap that explains a failure without having any implications for the self. Instead, one chooses the smaller of two evils. If I claim that my worn-out shoes, were the cause of my bad performance, I may be able to convince people that I am still a capable climber, but they will definitely not think of me as very well prepared anymore. The fact, that it is the persons subjective value of different characteristics, that determines which of two attributes is seen as more important explains why I was confused by people seemingly boasting about their lack of training. I have never seen myself as someone who is especially talented in climbing, but I have always been proud of being someone who works hard and trains a lot. Therefore, to me, a threat to my self-concept of being a hard worker is more severe than a threat to my self-concept of being talented and I tend to excuse a bad performance with a lack of the latter. On the contrary, a person who values being talented more than working hard will tend more towards the pattern described in the beginning and excuse a failure with a lack of training in order to preserve their self-image of being talented.

And the thing is: It works. At least in the sense that self-handicaps reduce the implications of a bad performance for relevant abilities and characteristics. But it has a price. It only works if the handicap is believable. That means whatever the handicap is, it has to be perceived as actually impairing one's performance. Going back to the distinction between the different kinds of handicaps: Claimed handicaps (e.g., exaggerating how little one has trained) are usually less risky, meaning that they are less likely to hurt one’s performance, but they are also less believable and more easily perceived as “just an excuse”. So, unfortunately, a self-handicap that is convincing will probably actually hurt one's performance. You don’t get to have your cake and eat it too. That is also where the problem for competitive athletes becomes apparent: Competitive sports are by their nature about performance and self-handicapping endangers it.

Therefore, if performance is the goal, self-handicapping has to be stopped. But as self-handicapping is usually at least partly unconscious that is not always easy.

An important strategy derives from the fact that self-handicapping usually only occurs if the person has a positive but fragile self-image. That means she is hoping to be good in whatever the characteristic or ability under consideration is but isn't quite sure. The self-handicap, as previously mentioned, shifts the perceived cause of a (bad) performance to a factor deemed less relevant. It follows that there remains a certain uncertainty about the actual subject and the confrontation with a possibly uncomfortable reality is avoided. If I had tried harder, I might have done that boulder. But if I had tried harder and didn't do it, I would have had to live with the fact that I wasn't good enough. The whole thing is quite similar to Schrodinger's cat: As long as the box remains closed the cat might still be alive. And if you work hard enough on your rationalizations you might even be able to convince yourself and everybody else, that it definitely still is. But if you open the box, and the cat is dead you’re going to have to deal with it. Therefore, if the uncertainty can be prevented from developing in the first place, the likelihood of self-handicapping can be decreased dramatically. This can be done by consequently seeking accurate feedback about one’s performance.

On the other hand, if nothing is done, a downward spiral of uncertainty, self-handicapping, and failure can develop. That is most easily seen when the handicap of choice is not training or giving your full effort. That strategy serves as a short-term guard against having to face the potentially uncomfortable truth of not being as good as one has hoped. But not training will have a negative impact on one’s actual abilities. Therefore, the next time around, facing this reality is even more uncomfortable, and avoiding it by the use of self-handicaps becomes even more tempting. And so the vicious circle takes its course.

Another possible point of intervention comes from the fact that self-handicapping only works properly if the motivation behind it remains hidden. Should it become clear that the person shows a certain behavior to excuse a possible failure it loses its effect. It's not unlike a soldier shooting himself in the foot to be released from service. If anyone finds out what he did, the whole thing will probably backfire. Therefore, uncovering potential self-handicapping behaviors and the underlying motivation is an effective strategy to stop it from happening. In most cases, it is enough to spell out what options there are, what the likely consequences of those will be, and explicitly giving the person a choice. Going back to the example of worn-out climbing shoes: If anyone would ask me why I didn't get new shoes since climbing with the old ones was likely to impair my climbing, I would either have to come up with another good reason or get a new pair and accept that the handicap was no longer usable.

And finally, in situations in which the social component is central (that is, the behavior is mainly about “Impression management”), it helps to ask oneself whether one would behave in the same way if no one else was present or if one has behaved differently in similar situations in the past when no one else was there. If, in doing that one notices discrepancies between the two this might also be an indicator that there is some self-handicapping going on.

However, in the end, nothing will replace taking a hard look at one's behaviors and doing a whole lot of critical self-reflection because, as is so often the case, the truth might be a little uncomfortable.

Additionally, I have included some of the questions from the self-handicapping scale, as it is often used in studies, down below. Not all items apply to sporting situations as the scale was originally developed for academic settings. Therefore, I chose the eight I found to be most fitting. If you should find yourself agreeing with a lot of these statements that might be an indicator, that you are prone to self-handicapping.

1. I would do a lot better if I tried harder.

2. Someday I might get it all together.

3. I would do much better if I did not let my emotions get in the way.

4. I sometimes enjoy being mildly ill for a day or two because it takes off the pressure.

5. I tend to get very anxious before an exam or “performance”.

Reverse Scored Items (High agreement indicates low Self Handicapping)

6. I tend to overprepare when I have any kind of exam or “performance”.

7. I always try to do my best, no matter what.

8. I would rather be respected for doing my best than admired for my potential.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Part III: Losing yourself – Injuries and the athletic identity

Injuries suck. I think everyone can agree on that. But especially for competitive athletes, injuries are often times more than just a nuisance, that temporarily keeps them from doing something they like to do. Athletes often experience a downright emotional rollercoaster after having injured themselves and during the rehabilitation process. Anger, resentment, anxiety, confusion, shock, helplessness and pretty much everything in between can occur. I certainly can say for myself, that I have gone through almost everything on that list in the past six months following my finger injury. In the most extreme cases an athlete might even develop a full-blown depression or commit suicide. These events do have more than one cause, probably including many that have nothing to do whatsoever with the injury. Nevertheless, injuries are one of the biggest risk factors for suicide in athletes.

To an outsider, such a reaction may seem completely unreasonable, especially if the injury is something that seems to be rather insignificant in the grand scheme of things, like a strained muscle, a broken bone or a torn ligament. These might seem like an unfortunate annoyance but hardly reason for such an extreme psychological reaction. However, one must realize that an injury has the potential to be a traumatic experience for athletes. For example, these individuals often experience symptoms following the injury, comparable to what people experience after having been in a fire or a natural disaster. But why is that?

There is certainly a whole range of factors that contribute to the high stress potential of an injury, including but not limited to the loss of the social environment and one’s daily structure as well as simply being unable to do something one loves. However, one central aspect is the identity threat that comes with being an injured athlete.

Usually, one’s self-concept consists of a variety of different self-constructs. For example, I have a self-construct of myself as a psychology student, which is primarily important at the university or when I am studying. On the other hand, at home my role within the family might come more into focus. The extent to which a person identifies with the role of an athlete and uses it for the purpose of self-definition is called the athletic identity. In many competitive athletes, this is – unsurprisingly – very highly developed. Why else would someone spend all those hours grinding through long sessions, continue climbing with bloody hands and squeeze into shoes that are at least two sizes too small. In general, a strong athletic identity is not something negative or to be avoided, on the contrary, it can have a variety of positive effects such as higher self-esteem and (not surprisingly, I think) better performance. I don`t think there was or ever will be a very high-level athlete that doesn’t identify with the role of an athlete to a very substantial degree. However, an injury essentially eliminates that source of identity and the person is suddenly confronted with the question: “What am I without this sport?” Now, the crucial problem arises, if the role of an athlete is the only thing a person uses to define herself, because in this case the answer will be: “Nothing”. From this perspective, it becomes obvious why injuries can evoke such strong psychological reactions that otherwise can appear to be completely out of proportion. If the sport is everything one has, life without it might not really seem worth living.

Now, the solution to this problem is not necessarily reducing one’s identification as an athlete. That might be sensible or even required if the injury is career-ending or one resigns from (competitive) sports for other reasons. By the way, in such cases, a similar phenomenon can occur, meaning, that individuals who up to that point have only defined themselves as an athlete are at risk of running into psychological and emotional trouble. This demonstrates that simply devaluating the role of the sport for one’s life is not a particularly good idea, as long as one does not have anything else to draw his identity and self-worth from. Furthermore, in most cases the goal is to get back to being able to train and compete, thus the importance of the sport is not to be reduced generally. Therefore, the solution is not giving up one’s identity as an athlete but creating additional sources from which to derive feelings of self-worth and identity. For example, during the past six months, while rehabilitating my finger injury, my university studies have helped me tremendously, as they gave me something aside from the injury to focus on, into which I was able to invest my time in and something to be proud of at the end of the day.

Part of the solution might already be shifting the focus away from the performance to the process of being an athlete. Often times, the real question – at least for competitive athletes - is not: “What am I without the sport?”, but rather: “What am I without my abilities and achievements?” In most cases, people can still train somehow, even while injured. However, if feelings of identity and self-worth are only drawn from the actual performance, that’s a small comfort. However, if being an athlete is defined as showing up for training, working hard and doing what needs to be done, an injury does not stand in the way of that all that much. And ironically, this very much increases the chances of returning to one’s previous level of performance faster.

This question: "What am I without my ability to perform?” is one that, for competitive athletes, is not only relevant in the context of injury. The very same question arises during times in which training is not going so well, whenever a competition goes wrong and of course sooner or later when one ends his or her career. Therefore, in my opinion, it is absolutely essential for every athlete to have an answer to this question.

When I started competing, my youth coach once confronted me with this very same question (at least indirectly) and to be honest, back then I did not have an answer. I have always been someone who in nearly all aspects of life identifies in terms of my performance and the prospect of losing that was pretty scary. But over time I have learned to shift that focus. Three weeks before I injured my finger and immediately prior to the only two competition of the “Covid-Season” 2020, I tweaked something in my back and for a couple of days was not sure whether I would be able to start. In the six months leading up to that I had not missed a single day of training, I was stronger than ever before and suddenly I wasn't sure whether all of that might have been in vain. But I did not regret a single one of those days. And in that moment, I knew I had an answer. That does not mean I was not very much annoyed initially and quite relieved once it turned out I was able to compete after all. The same goes for the past six months, in which I had to deal with my finger injury. It has been anything but easy, but not because I felt like I needed to perform in order to be someone, but simply because I love climbing and being able to try hard and I simply missed that a lot.

An athlete should never define him or herself only in terms of achievement and performance. Making one's whole happiness, identity, and feelings of self worth dependent on what one is able to do physically, potentially even restricted to a couple of competitions a year is a recipe for disaster.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

PART II: Climbing with Galatea and Pygmalion – The Power of Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

“Whether you think you can or you think you can’t - You are right” – Henry Ford

The following text is something I wrote on an Instagram post back in January of 2018 accompanying a video of a simple run and jump style boulder: "A year ago, I wouldn't have dreamed of doing a boulder like this. I was afraid of jumps and parkour-style boulders, avoided them wherever I could and when there was no way around it, I usually failed miserably. And my biggest mistake was probably that I kept telling myself that I was horrible im jumping and I couldn't change something about it anyway. Then, last year at the Berlin championship's the last boulder in the finals was a small, easy Run-and-Jump. Basically everybody did it, except for me. I barely moved out of the starting position. This was the turning point for me. After the comp I decided I had to change something, I couldn't just go on like that with such an obvious weakness. So I started practising. At first it was terrible, I must have looked like a complete idiot, trying to jump without actually moving. But after some time it got a little bit better, and as I got better it started to be more fun. And because I had more fun I did it more often. And because I did it more often I got even better...

Today, I wouldn't go as far to call jumping my strength, but it got a lot better and I'm pretty comfortable with them now. And guess what, it is actually a lot of fun. But the most important thing was, that I stopped telling myself, I can't jump and that really goes for everything. As long as you tell yourself you can't do something, you won't be able to do it."

I included a video of the boulder in Berlin last year, but I warn you, it's horrible...

I included a video of the boulder in Berlin last year, but I warn you, it's horrible...

Since then, even more time has passed obviously, and coordination problems and dynos have actually become one of my greatest strengths. Cleary I was not doomed to suck at them forever. So why did I believe I was for such a long time? The answer lies in a phenomenon that is called a self-fulfilling prophecy or an expectancy effect.

Self-Fulfilling & Self-Sustaining Prophecies

Self-fulfilling prophecies are initially false beliefs, which, however, cause a behaviour that does make the expectation become true. The initial conception can both be too positive or too negative, in the end self-fulfilling prophecies simply initiate a trend.

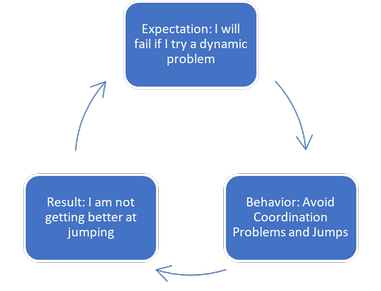

Most of the time, however, none of the parties involved actually realizes how they are shaping their own reality. On the contrary, fulfilment of the prophecy is seen as confirmation of one’s competence in judgement, thereby increasing the confidence in future predictions and the strength of the effects following from them. This has the potential to create – depending on the original expectation – a vicious or a virtuous cycle.

For example, in the past, due to my height and inability to do dynamic moves, I always preferred static solutions to boulder problems. This led to me practicing any sort of coordination style movement even less. That lack of training in turn showed in my results and bolstered my self-perception as a bad “Jumper” including the assumption that I should, whenever possible, prefer static solutions. However, once the trend started reversing and I became better and better, my self-concept shifted, as I was now seeing myself as a good “Jumper”. This in turn led to me preferring dynamic solutions more often, thereby practicing them more and more and becoming even better.

Another incredibly common instance in competitive sports is found in people who are afraid of failure in competitions. The expectation of failure causes stress and distracts from the actual task, thereby actually increasing the probability of a bad performance.

To delineate from the self-fulfilling prophecy is a self-sustaining prophecy. In this case, there is a valid basis for the original assumption. In practices, however, these two are often hard to distinguish. Often times, the original expectation is based on a kernel of truth. Likewise, a self-fulfilling prophecy can become a self-sustaining prophecy, once it has created a certain reality, thereby sustaining it.

Pygmalion & Galatea

Furthermore, two types of self-fulfilling prophecies can be differentiated: If one’s own beliefs are causative of the effect, the phenomenon is called a Galatea effect. If, however, the cause lies in the expectation of another person, e.g., a coach or a parent, this is referred to as a Pygmalion effect.

A Pygmalion effect can occur, if the belief in an athlete’s talent leads to him or her being supported and encouraged a lot. On the other hand, if athletes that are not seen as having potential might not be supported to the same extent or will not be nominated for key competitions. Galatea and Pygmalion effects can be hard to distinguish as well. They may also be in operation at the same time or a Pygmalion effect might be mediated by the transfer of said expectations on to the target.

Using expectancy effects

It is possible to actively use the power of expectancy effects, as they can exert a motivational pull: High expectancies lead to more motivation and training, which lead to higher abilities and better performance which in turn increase expectations again. However, in order to do so, it is necessary to intentionally construct and design the underlying narratives and expectations.

The first step in using expectancy effects deliberately is always to become aware of their possible effects and mechanisms. This enables one to identify existing assumptions, which might be having unwanted effects and change the corresponding beliefs and narratives so that they become beneficial. How exactly this is done will always be specific to the situation and the goal, however the following strategies can serve as guidelines.

- Self-concept: One’s self-concept answers the question: “Who am I?”. As long as the answer to that contains certain abilities, behaviours and also weaknesses as an integral part of the own person, it is very difficult to escape the vicious cycle of a self-fulfilling prophecy. To utilize expectancy effects, the self-concept has to be re-designed accordingly: Unhelpful self-constructs have to be changed or eliminated and beneficial conceptions of the own person have to be developed. This will take a lot of time and effort, but it is the foundation, as expectations are a direct consequence of one’s self-concept. As long as they remain unchanged, everything else is merely tinkering about with the symptoms, as the existing beliefs will continue to pull the behaviour towards them like a magnet.

- High goals: Even if one – be it as an athlete or as a coach – is sceptical whether high goals are appropriate, one should set them. High (and preferably specific) goals have shown to be conductive to higher performance in psychological research time and time again, as they raise the standard and demand more until satisfaction can set in. Negative expectancy effects can work the other way around. The person sets only very minor goals or none at all. As a consequence, they do not demand much from themselves, don’t improve and et voilá, the prophecy is fulfilled.

- Process goals: High goals can easily be perceived as unrealistic. Similarly, it is very difficult to escape the vicious circle of a self-fulfilling prophecy once certain habits and behaviour have become ingrained and weaknesses have developed, since the expectation, is, at least somewhat, true. In this case the solution is not to sugarcoat things or deny the existing problems. On the contrary, that would be counterproductive. I didn’t start the process of learning how to do dynamic movements by persuading myself I was good at them either.

- Instead, goals should be oriented on the learning process and aim at showing a way out of the downward spiral. For instance, I could have set the goal of doing a certain number of jumps and coordination style boulders every week.

- Intermediate goals: Furthermore, it is helpful to divide the overall goal into smaller subgoals. Again, I didn’t start by trying triple dynos. I started by practicing the easiest jumps imaginable. And once I improved, I started double dynos. And once I had mastered those, THEN I started working on triple dynos. Starting off with the end goal is more likely to cause frustration than anything else, since the discrepancies between the current situation and the target state can seem insurmountable. If, however, the process is divided into many smaller segments, each intermediate goal is doable and the overall goal will become less intimidating.

- Effort-Performance-Contingency: An implicit assumption, which is usually part of a self-fulfilling prophecy, especially if it is a negative one, is that one is simply unable to improve in certain things, regardless of all the training and effort. This again keeps one from actually training, because why invest all of that time and effort, if it won’t lead anywhere. More often than not however, this assumption is untrue and is actually quickly recognized as such if it is actually stated openly. To counteract this, it is important to remind oneself again and again, that performance and improvements are, to a very large part, dependent on the investment one makes. At the bottom of it, it is about substituting the belief: “I’m not good at XYZ because I am simply not made for that” with “I am not (yet) good at XYZ, because I haven’t invested the necessary time and effort.” That does not mean anyone can achieve anything or that effort is the only determinant of performance. There will always be people who are naturally gifted in certain things, while others have a really hard time with it. However, one will almost always be better off when making the necessary investments in terms of time and energy.

- Self-handicapping: Self-handicapping is a central mechanism by which negative expectancy effects can operate. Self-handicapping is defined as behaviour that undermines one’s performance and capabilities in order to be able to excuse a possible failure in advance. Examples include the avoidance of training, downplaying one’s abilities or even the consumption of alcohol and drugs, especially right before a competition. Although these behaviours can serve as justification for a bad performance, they objectively increase the risk of that very same thing happening in the first place and therefore should be stopped. This can be very difficult, since often times these mechanisms operate subconsciously and have become very ingrained, but in order to fulfil one’s true potential it is absolutely necessary to eliminate these behaviours.

- Selective Training: The avoidance of training can – as described – be a used as a self-handicapping strategy. However, a lot of times, athletes will simply spend more time and energy training those aspects and abilities they are already good at, because that is – usually – also the most enjoyable part of training. On the other hand, comparatively little time is spent practicing the things that would actually require it the most, since almost nobody likes working on their weaknesses, especially in front of other people.

However, with all these mechanisms and their situational differences, it should never be forgotten that in the end, the important consequences are in the behaviour. Therefore, it is of central importance to identify the exact points on which expectations influence actual behaviour, in order to understand how these effects are operating and to counteract them if necessary. For example, I might realize that my expectations keep me from practicing a certain style of boulder problems because I am afraid to embarrass myself. In this case I will (hopefully) do something about it, maybe by blocking out certain times of my training, during which the gym is relatively empty, just to focus on that. At the same time, it is obviously necessary to start working on those underlying beliefs and assumptions but waiting until they have changed to start modifying the training is not a great strategy. Instead, both should occur at the same time, in keeping with the motto: “Fake it till you make it”. This can also initiate an upward spiral, as performance improvements due to the training will make it easier to modify beliefs and changes in beliefs and therefore expectations will make it easier to improve.

Similarly, the transfer of expectations from one person to the another is also just possible via behaviour, be it verbal or non-verbal, extremely obvious or incredibly subtle. For example, a coach can openly tell an athlete, that he does not think the athlete will ever get anywhere. But he could also express his expectations by setting low goals, not paying much attention during training sessions or not reacting surprised after setbacks or subpar performances. In these cases, the responsibility for identification and intervention is on both the coach and the athlete, in extreme cases that might even mean switching coaches. The same obviously applies for parents and other important persons (although finding new parents is obviously not an option).

However, regardless of the source and the type, expectancy effects can be incredibly powerful. If left unchecked they are able to create a crippling vicious cycle. On the other hand, if they are used intentionally they can create an equally impressive upward spiral and it is up to each and every one of us whether we will use them to bring out the best in themselves and everyone around us.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

PART I: Would have, could have, should have – Counterfactual thought in competition climbing

Bouldering nationals this year didn’t even go really bad in terms of the result, but I felt I made quite a few avoidable mistakes in semis. I ultimately ended up in eighth place, two attempts out of finals and everyone who has been in a similar situation can probably imagine what went through my head during the long train journey back home: “If only I had been a little more patient, I could have done that Boulder first try.” “If only I had positioned my feet a little more carefully, maybe I wouldn’t have fallen off.” “If only I had thought of that beta a little bit earlier” Would have, could have, should have…

Counterfactual thinking and its directions

These kinds of thoughts have been termed counterfactuals and as the name implies, they are about things that could have happened but didn’t. Psychologists distinguish two types of these: In upward counterfactual thinking, a situation is imagined that is better than what happened in actuality. My thoughts after nationals are perfect examples of this category. In contrast to that, downward counterfactuals involve a scenario that are worse than reality, e.g. “At least I did the slab on my third try and didn’t slip again”

Counterfactual thoughts are very common after competitions which is due to the characteristic circumstances of sporting competitions. Psychological research has identified many factors that influence whether and how much counterfactual thinking occurs, what its direction is (upward or downward) and what its specific content is likely to be. Therefore, the following list will only contain those which are most relevant to the competition setting and are able to explain why many athletes spend so much time on – mainly upward – counterfactual thinking after competitions.

Triggering factors

Need for correction

Counterfactual thought is especially prevalent in situations that demand corrective action such as a negative event, a failure, or a missed goal, all of which are integral parts of competitive sports, since high expectations and the continual search for possibilities to improve are in its very nature.

Closeness

Counterfactuals are also more likely to occur, if – in hindsight – it seems as something else “almost” happened meaning another outcome was “closely” missed. This is especially often the case in high-level bouldering competitions with a very dense field, as the smallest differences in movement or beta can have a very large effect on the final ranking.

Exceptionality

Furthermore, counterfactual thoughts are more probable following unusual or exceptional occurrences. Due to the high volume of training, competitive athletes usually know themselves and their strengths and weaknesses very well, which is why they tend to be very accurate at assessing whether or not their performance was “normal”

Controllability

Counterfactuals tend to focus on aspects of the situation that are perceived as controllable. As most (successful) athletes possess an internal locus of control, meaning they interpret events – positive and negative – as consequences of their own behaviour as much as possible, they usually perceive their performance and result as highly controllable.

Obviousness

The more obvious an alternative event is, the more likely it is going to be subject of a counterfactual. In competitions these possible alternatives are made very salient by the explicit comparison between one’s own performance and those of others.

Repeatability

If an event or something similar is likely to repeat, upward counterfactuals tend to predominate. As most comp climbers probably plan on participating in competitions in the future, this is the scenario they find themselves in. If, on the other hand, the occurrence is seen as a one-time happening, the following counterfactuals will likely be mostly downward.

Looking at these factors it becomes very apparent why I spent so much time wrapped up in counterfactual thought after nationals. First of all, there was obviously a need for correction because as I said, I was quite dissatisfied with my performance. Furthermore, I intend to continue competing, therefore there will likely be similar occurrences in the future for which I would like to be better prepared. Moreover, a better performance and specifically making it into finals was incredibly close as I fell while matching the top hold on the last problem in semis. Moreover, there weren’t any interfering factors, therefore it is clear to me, that the only person responsible for that result is myself. And on top of all that I was watching the finals livestream on my train ride back home, which was a continual reminder of what could have been. Really the only factor that wasn’t involved was Exceptionality.

Functionality of Counterfactual thinking

Counterfactual thoughts, however, are not just simply there, they can influence future performance. To utilize them, athletes can be instructed or self-instruct to generate certain counterfactuals, but in order for these to be functional – that is to contribute to improvements – the following three criteria need to be met.

Identification of the correct cause

In order for performance improvements to take place, accurate knowledge about the reasons of previous ones – both good and bad – is needed. Counterfactuals are in essence a type of causal reasoning and as such can provide this knowledge and therefore indications which measurements can and should be taken. However, if the counterfactual is based on a causal assumption that is simply wrong or of little importance, any measures derived from that will have little or no effect on future improvements. Another problem is that the analysis of a problem is often terminated prematurely and something that is actually only symptom of a deeper problem is misidentified as the cause. The identification of the correct cause is made even more difficult by the fact that some of the factors that influence counterfactual thinking described above do not necessarily correlate with actual relevance, meaning one tends to focus on aspects that are not really significant. This is often further aggravated by the fact that there are no quick-fixes for the main success factors. Therefore, counterfactual thinking absolutely requires critical self-reflection and awareness of one’s biases.

For example, often times situational circumstances such as the weather or the time of the day are made responsible for an unsatisfactory performance. But since all athletes are faces with the same conditions that cannot be the actual cause. If anything, the persons inability to cope with these circumstances is. More often however, these kinds of explanations are simply excuses for not having to deal with the real causes.

Check controllability

If the counterfactual accurately identifies an antecedent cause but this cause is simply not under control of the individual that information is of no value. Functional counterfactuals on the other hand focus on what one personally could have done to improve the performance.

A classic example of this is the discussion about height. It may very well be true, that on a specific problem or in a certain competition height was the decisive factor, but one simply cannot change one’s own height.

In that, however, it is also important to question whether factors one considers to be outside of one’s personal control really are or whether there might not be something one could do.

E.g., many athletes rarely work on their mental game, partly due to ignorance but often because they consider their own thoughts to be uncontrollable. This, however, is not the case and even if one doesn’t initially know what to do about it there is always the possibility to get help and thereby gain control.

Transferability

If the causal relationship identified be the counterfactual is not applicable to any future situation or the athlete does not recognize the appropriate circumstances when they arise, counterfactual thinking will not be of any use, as even though counterfactuals are concerned with events in the past, in the end they can only influence future performances.

A personal example for this is my (unfortunate) tendency to forget whether or where a hold is located on a volume that you cannot see once you’re on the wall. This has costed me more than one top already in competitions and I’ve spent a lot of time dwelling on these, yet it happened to me again and again because in the moment I do not realize that now would be the time to apply this hard-won knowledge and memorize where exactly that hold is.

Affective and motivational consequences

Aside from the purely cognitive effects discussed so far, counterfactual thinking also has affective and motivational consequences. In most cases, downward counterfactuals will make one feel better while upward counterfactuals will make one feel worse. Especially the feeling of regret is associated with upward counterfactuals. This negative affect can be quite motivating under certain circumstances and has often contributed to improvement in performance in lab studies. However, as the effectiveness of this strategy depends on several constraints and as excessive upward counterfactual thinking and regret are associated with depression, I think using counterfactual thinking as a long-term motivational strategy is rather risky. Furthermore, most competitive athletes do not have a lack of motivation which would make its use necessary anyway. Downward counterfactuals on the other hand, while making one feel better, also suggest that there is no need for action and thus facilitate complacency which is not a basis for performance enhancement either.

Conclusion

As a result of that, it makes more sense to use counterfactual thinking as a short-term and primarily cognitive strategy in order to identify causes and draw conclusions from the events. To ensure, that the thinking stays functional and doesn’t drift off into pointless wishful thinking it is important to take a very intentional approach. To guarantee that this will happens, the following strategies are helpful

- Critical self-reflection and honesty: Both are absolutely necessary to check whether an assumed cause is actually correct.

- Talking to another person: Four eyes see more than two. Furthermore, it is often difficult to admit to one’s own weaknesses and confront uncomfortable truths, which is why it can be very useful to go through that process with someone else. However, this person has to be able – at least in this situation – to be brutally honest, because if instead of speaking the truth this person tries to avoid hurting any feelings, it whole point is missed.

- Backtracing chains of causation: To ensure, that the identified cause isn’t just a symptom of an underlying problem, causal chains should be backtraced as far as possible or reasonable. At the same time, this can be used to check, whether something one believes to be uncontrollable, actually is or whether there might not be some place or possibility to intervene.

- Focusing on one’s own possibilities for action: In order to make sure that any factors under consideration are indeed inside of one’s control, ultimately it is only helpful to focus on one’s own possibilities and actions. However, as described above, counterfactuals tend to focus on these aspects anyway, nevertheless it is important to keep this in the back of your head.

- Establishing habits: The biggest threat in regard to the applicability of the new-won knowledge is usually, that situations in which it would be relevant are not recognized. To prevent this, it is necessary to establish habits that guarantee the necessary action will be performed at the appropriate point in time either by automating it or using reminders.

This list is obviously be no means exhaustive, bit these are the strategies, that seem the most useful and have helped me the most. However, in the end it is only important, that all necessary information is extracted out of what happened, learn from it and after that forget about it and focus on the future. And yes, it often is difficult to stop having these thoughts, but (especially with a lot of practice) it is possible.

Kein Kommentar